Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition of 1914-1916 remains one of the most incredible survival adventures of all time. Ignoring warnings of worsening pack ice, Shackleton and his crew of 27 men attempted to become the first explorers to transverse Antarctica through the South Pole. Sailing December 5, 1914 from a South Atlantic whaling station on the aptly named Endurance, their ship soon became trapped in an ice floe with Antarctica in sight. Carried hundreds of miles away by the currents, ten months later the Endurance was crushed by ice and sank leaving the men stranded on a large flat floe with only their supplies and three small lifeboats.

Eventually, the crew reached open water and was able to sail to an uninhabited island. From there, Shackleton and 5 crew members traveled across 800 miles of rough seas to return to the whaling station for help. Landing on the opposite side of the island, they crossed glaciers, mountains and waterfalls on foot to finally reach the port. Four months and several rescue attempts later, they returned to the uninhabited island and rescued the remaining 22 men. Incredibly, not a single crewmember was lost over the 20-month journey!

“Part of what the Shackleton story is about is leading under moments of great uncertainty when the game is changing and may change on a dime” says Harvard Business School Professor Nancy Koehn who created a business case about the Shackleton expedition. “He’s tireless, he’s a very fascinating example of entrepreneurship, of self-promotion, of obsessive dedication to a goal.”

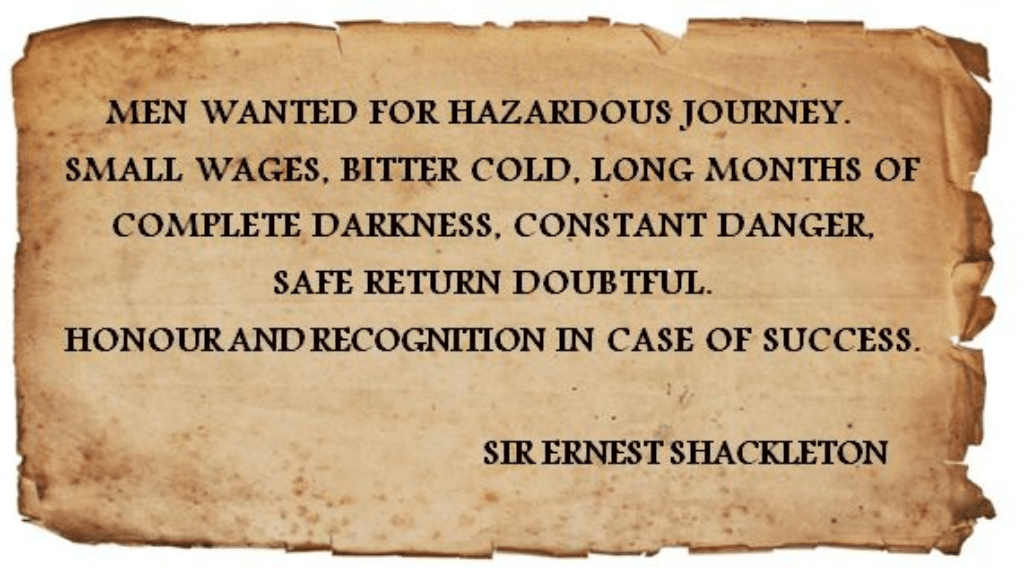

Shackleton’s recruitment notice above reminds us that careers in academic science are also filled with their own unique hazards. Although the vast majority of us will never endure the life-threatening dangers faced by the crew of the Endurance, fewer than half of those who earn their doctorate within a scientific field will land in a tenure-stream positions within that area. Moreover, with too few university jobs and far more scientists competing for a limited supply of money to support them, many graduates are simply giving-up on a career in science.

Since I attended my first SBSM Annual Meeting in 2000, I have had the privilege to meet many SBSM members at various stages in their careers. Several were or became presidents of SBSM (see Past Presidents List) and were recognized during our Society’s 75th Anniversary celebrations, and all helped guide me to safety and minimize the rough patches of ice in my career.

“80% of success is just showing up.” I have long attributed my success with getting my cardiac projects funded to my involvement with SBSM (see 45:20 of my personal “voyage of endurance” here). The opportunities to learn about cutting-edge work a year or more before its publication; present posters and oral presentations for feedback; contribute to the scientific discourse; and form lasting relations with colleagues at other universities have had tremendous impact on my career success and satisfaction. These activities have also inspired me to stay engaged with SBSM for nearly 20 years and promote the value of the organization to others.If you are in your research training or in a new faculty position, I strongly encourage you to apply to the APS Young Investigator Colloquium where you can form lasting relationships with senior psychosomatic medicine investigators and peers from outside your institution who can guide you on your voyage of endurance (see my last month’s column).

Regardless of your career stage, submit an abstract for presentation at our next Annual Meeting to be held March 5-6, 2019 in Vancouver, BC (due October 20, 2018).

And if you don’t have a paper to present, come to Vancouver anyway to learn about the latest trends and discoveries in psychosomatic medicine or simply to catch-up with friends and colleagues and enjoy the city.

I hope you are having a great summer!

Bruce L. Rollman, MD, MPH

President, SBSM 2018/19